WildFishGems robbed

Posted: November 3, 2023 Filed under: Europe, Good and Evil 7 CommentsOur inventory went up the safe wall and through the roof, past cameras and alarms.

Twenty years of work PUFF – gone. No insurances were available in Europe, only USA.

The website will shut down soon. Copy content that you may miss later.

Thank you all for your kindness over the years. It was a pleasure working for you, almost always 🙂

Sorry, I did not have time to answer the many messages I received before our account was closed. Your compassion was the only bright spot in these sad days.

Edward Bristol

Adventures of a Gem Trader. Book III

Posted: July 31, 2022 Filed under: Asia, Good and Evil | Tags: gem trade, Thailand Leave a comment

Greed is like salt.

Some must be.

Too much, ruins more than soups.

Alexandrite Farming in Thailand

South of Bangkok, September 2003

Ed stared over an endless stretch of swamps glimmering in the hot afternoon sun. The ugliest man in the world shared from deep inside his ego: how he had the genius to do what would come anyways; how his was the success of Asian cunning and Western determination, or vice versa. The man droned on, readying an old video cam. Lizzy stared at the fan standing in a corner, slowly churning the thick fragrant air.

Part 1

Sri Lanka, 2002

On the island once called Ceylon, decades of civil war came to an end. A peace treaty, supported by India and brokered by Norway, had been signed between the separatist Tamil Tigers in the North and the Sri Lankan government.

Ed and Lizzy moved ‘Wild Monkey Gems’ from Kenya to Sri Lanka and settled in Batticaloa, deep in Tamil Tiger territory where Ed had spent parts of his youth. For years, only NGOs had dared to show there in convoys of shiny SUVs. The new arrivals were gawked at like aliens, the first foreigners to settle on the North coast for over two decades, not war-journalists but normal businesspeople, private investors daring to start a new life. Though they encountered many cynics and much disbelieve, some saw in them a sign that better times were coming, finally.

Their website produced regular orders which they exported through Sri Lanka’s Gem Authority. Each gem underwent detailed documentation and needed a dozen signatures before it was sealed, under witnesses, in hand-made tin-boxes and handed over for shipment.

In a rented house, they lived without dairy products, chocolate, olive oil or steaks. Instead, they ate rice, mixed with unforgivably spicy curry sauce and sprinkled with the fine sand Batticaloa was built on.

They discovered a country frozen in war-torn backwardness. Modernity had simply passed-by the Northern highlands. Elephants worked for their lively hood, not for tourists, men hunted in the waves like their grandfathers had, and walking was still the common mode of transport. Travelling the mining areas, they stayed in guest houses where coffee was unknown, the restroom was a hole in the floor, and villagers came in droves to gawk at the ‘black woman’, Lizzy that is. Untouched natural beauty lay interrupted only by the terrifying scars of war, burned down villages, pillboxes on strategic corners, and bombed-out hotel cadavers. People had suffered, with traumatized eyes, fear and loss carved in their faces, yearning for normality, hungry to catch-up with the rest of the world.

In September, they met Peter Pestana, the CEO of OneOre and their angel investor, in a Colombo hotel. Post 9/11, his hair had thinned and greyed, but he still wore it shoulder long. Other than aged, he had remained the imprint of wealth, smiling with the confidence of London, well fed, and refreshed from his private jet. Lizzy and Edward had aged, too, but weren’t well fed and looked as if they lived deep in the jungle, which was indeed true.

In his presidential suite, Peter indulged them with Australian steaks, fresh orange juice and later cheesecake and dark chocolate. One must have experienced months of sandy rice with spicy sauce to really appreciate a steak, salted butter, and fresh bread.

When both surrendered with bulging bellies on a silk sofa, Peter got down to business. He did not ask for their sales data, which Ed had prepared in some detail, but brought out a small velvet bag and showed an extra fine Alexandrite, near five carats with the much sought-after ‘dramatic’ color-change, moving from jungle green to a crimson red.

They had never seen such quality and said so. To their surprise, Peter did not look happy but shook his head as he pulled out a bigger bag with twenty more stones of similar size and quality. No collector would have transported such gems in one bag, tumbling and chipping facets, but Peter’s carelessness and the parcel’s conformity could only mean one thing: They were not natural. With a disrespectful motion, Peter spilled the whole bag onto the glass table.

“Synthetic?” Ed asked doubtfully. So far, all synthetic alexandrite he had seen were ugly ducks.

“Nope,” Peter said. “These are really Chrysoberyl. My lab can’t figure out how they were treated. Undistinguishable from Alexandrite. I must expose them. Every day these guys sell undisclosed into the market, is one day lost.”

Peter paused and looked at his guests.

“I need an undercover buyer to go to Bangkok and find the source, or I have to depreciate my 25 million euros stock in Alexandrite.”

Ed and Lizzy exchanged glances. Lizzy nodded ever so slightly.

Part 2

Two days later, Peter flew them to Bangkok, and immediately ordered his pilot to continue to London.

They had reserved a room at The Lebua State Towers and were lucky to get a residence on the 55th floor overlooking buzzling Bangkok as far as the smog would allow. The Chao Praya, the ‘big river’, snaked majestically beneath their balcony, boats flitting left and right like toys, the city thrumming with life day and night.

Next morning, they walked Silom, the street every gemstone visits at least once on its way from mine to jewelry. Asking for high-end alexandrite, they were shown five stones of excellent quality, in quick order, each seller claiming that his was the best gem found in recent history. For reference, they bought two pieces, already far under normal market value, a sure sign that depreciation had begun.

Those days, gem business on Silom was conducted in hard cash, best in dollar or euro, while tax invoices and export papers were written out in Thai Baht and thus at one percent of true value. Peter had supplied them with two-hundred banknotes of five hundred euros each, the highest cash denomination in the world. In Bangkok, a maid cleaning luxury apartments worth millions of dollars, would earn only one of these bills per year. Peter had also given the couple a credit card running on One-Ore. Unlimited funds, he had said.

In the evening, they sat in the cool breeze on the hotel’s rooftop bar, drank cooled Chablis, and watched the fancy city-crowd partying, a stark contrast to Batticaloa where most evenings ended with blackouts.

On the second day, they returned to the most ambitious Alexandrite dealer operating from a reserved table at a coffee bar. The Thai, with more rings than fingers and an open shirt revealing a hairy chest, was delighted to see them again. They asked him for an introduction to his supplier. First, the dealer refused, but they insisted, saying they would not buy again unless they could meet the source. In the end, the man agreed and promised a meeting after lunch. This was another sign that something was afoot. No dealer would, under normal circumstances, disclose his source, because once he had introduced buyer to seller, they would push him out. But these weren’t normal circumstances. The quicker the buck, the better.

After lunch, the dealer took them to the VIP elevator of the Jewelry Trade Center, or JTC for short, and up to the top floor. There, they were introduced to Mr. Sandaporn, an elderly Thai-Chinese in dark suit and promenaded grey hair. With a nod, that guaranteed his provision, Sandaporn dismissed the Thai and led the couple into his inner office. Thick carpets, heavy dark wood furniture and curtains insulated the room from the ever-blaring city with the calm and quiet of a deep cave. After some small talk, Mr. Sandaporn presented a tray of four dozen perfect Alexandrite. Nature would not release such a selection in a century of earnest mining. When Lizzy, to Ed’s shock, remarked thus, Mr. Sandaporn shrugged and smiled.

“New mine,” he lied with perfection, didn’t even blink.

‘New Mine’ was always the explanation for new treatments. Ed knew these old traders for the sneakiest businessmen on earth. If good for sales, they would lie twice while saying ‘Good morning’ and be proud of it. Not a sign of bad character at all. Loyal friends and loving fathers they may be but cheating for profit was a sport to them.

To divert attention from the Alexandrite, Ed asked to see some red Spinel. When Sandaporn went to call his assistant, Lizzy shot a closeup of a framed desk photo showing the man shaking some VIP’s hand.

They bought a Spinel, together with one ‘New Mine’ Alexandrite, and promised to be back.

“We need help,” said Ed as they descended in the elevator.

A phone call later they had an after-hour appointment with Mr. Spy on Sukhumvit road.

Lizzy made jokes about the detective’s name, but Ed assured her that Mr. Spy was worth his money, and never gave up on a case, a pro in a world of amateurs.

The journey across the city took almost two hours by taxi and they swore to switch to the Bangkok-Sky-Train or BTS next time.

“Why didn’t we take somebody close-by?” asked Lizzy during the second hour in the smelly Taxi.

“Sukhumvit is not connected to the trade. We cannot discuss this anywhere near Silom.”

Mr. Spy was half Thai half Australian, a common enough mix in Bangkok. His dark-orange suit crowned by a yellow tie seemed to defy under-cover work, but the man could blend into local crowds like a lizard into the jungle. He had the thick black hair of most Asians but with a Caucasian wave. His eyes, too, had the elongated Asian shape but with the blue-grey color of a northern sea.

The PI listened patiently to Ed and Lizzy telling a couple’s story while he downloaded Sandaporn’s image to his laptop.

When they had finished, he said, “Sounds interesting. You are aware that I know dud about gemstones, right?”

Ed nodded. “Better so, they will not see you coming.”

Mr. Spy named his per diem rate and suggested a success bonus for locating the treatment facility.

“When can you start?” Ed asked before he accepted the offer.

“I do have other clients, but nothing pressing. I will research a bit tonight and start tomorrow.”

“Can we help?” Lizzy asked.

Mr. Spy studied his new clients for a moment, then waggled his head and began to rummage through a desk drawer. He came up with a little box from which he extracted a large coin, ten-baht with a copper inlay displaying the country’s King.

He handed the coin to Lizzy, who passed it to Ed after a study and a shrug.

“Go again to Mr. Sandaporn, tomorrow, and place the coin anywhere in his room. Can do? First thing in the morning?”

Before they left, Ed said, “Idea: I could ask for an unusual cut Alexandrite, something he won’t have, something he needs to order, perhaps you get closer that way.”

Part 3

The next day, Mr. Spy stationed himself near the VIP elevator. He spotted Sandaporn as he came to work punctually at 10.00.

Lizzy and Ed were already waiting in his front office when Sandaporn arrived. The trader ordered three iced lattes before he motioned them to enter his office. Ed began by praising the fake Alexandrite and asked to see more. As agreed with Lizzy, there was no further talk of impossible quality, even if it outed them as utter tourists. Burning $1.5k per carat on fakes, hurt Ed’s professional pride like a boxer taking a dive in round two.

Since the previous day, two rows of alexandrite had disappeared from the tray. Business, obviously, was brisk. Others were buying Alexandrite at depreciating prices and selling them into their sales channels for the original value. The flash supply created a wave of gems rolling towards the consumer market. To keep up the good mood, the couple chose twenty-one carats of Alexandrite in five more pieces.

When their iced lattes arrived, Ed used the commotion to drop Mr. Spy’s coin into a potted palm tree.

“Would you have a pair of trillions? Perhaps four carat each?” Ed asked, innocently sipping his latte.

Alexandrite was almost never cut in trillions because it sacrificed weight in favor of a mediocre brilliancy. Demanding a pair of such stones was asking the near impossible. Yet, Sandaporn didn’t blink, only checked his weekly planner, and said ‘yes’, he could have a pair of trillions in two days.

“We’ll be back for the pair day-after tomorrow,” Ed confirmed as they left. “Shall we make a deposit for the unusual cut?”

Mr. Sandaporn waved his hands. “No, not from my distinguished customers. I will have them ready. No problem.”

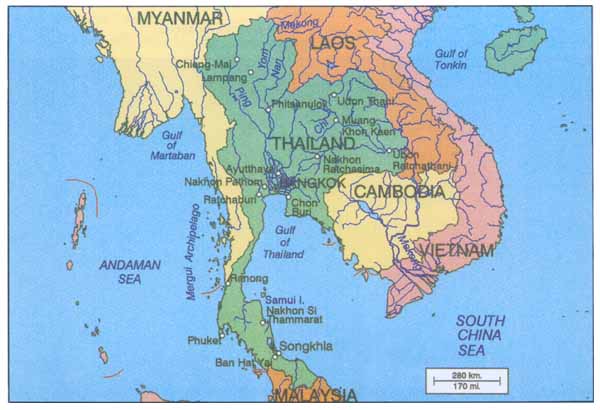

Below, in a coffee booth with view of the VIP elevator, Mr. Spy smiled. He listened to headphones, like so many, only that he carefully tuned a small black box hidden between his knees. Ed had guessed that the treatment facility would be located outside the city limits or South, in Bangkok’s secretive little sister, Chanthaburi, where most treatment factories were located. For that eventuality, Mr. Spy had reserved a rental Toyota Camry, already waiting in the JTC’s garage. Following a target on foot around Silom or in the BTS would be easy, but if Sandaporn travelled anywhere by car, Mr. Spy had to know the destination beforehand. Bangkok was far too chaotic for a spontaneous tail by car. The JTC’s garage alone had six exits onto four different streets depending in which direction somebody would want to leave town.

Later, Ed and Lizzy met Mr. Spy in a Starbucks inside the JTC.

“He has already ordered the special cut, then he made travel arrangements,” said Spy.

“Did he say where to?” Ed asked.

“Not exactly, but South, I think. He told his wife he’ll buy shrimps and be back for a late dinner.”

“Then it must be in Chanthaburi. A tough trip for one day though. Poor driver.”

“No. He told his driver to take a day off,” the PI said.

They agreed to stay in contact via text messages, for mobile reception could be spotty on the road.

Ed and Lizzy went to dine in the ‘Blue Elephant’, the newest opening of a French chef who had made a fortune with a European chain of none-spicy Thai restaurant visited by everybody except Thais.

The next day, at ten o’clock, a message from Spy reported Sandaporn arriving in his office.

“He has to get going, or he’ll never make it back in one day,” Ed remarked.

Chanthaburi was near the Cambodian border, a good six hours of hard driving, one way.

At eleven thirty, Mr. Spy messaged that he was leaving town by car, following his target. During lunch in a food court, a third message arrived: ‘Highway 3 to Chon.’

Back in the room, they studied a map. Highway ‘3’ lay South, towards Pattaya.

“But, no, he is not going to Chanthaburi,” Ed said. “That would have been the ‘361’. What is he doing?”

“Perhaps he goes to visit his little friend in the South, buys shrimps, and somebody else picks-up the gems?” asked Lizzy.

“No, yes, normally yes, Sandaporn has runners, but for a new treatment like this, he will keep the circle very small. He lies to his wife, even the driver is not supposed to know. That’s very secretive. Drivers normally know everything.”

On the map, Ed followed highway ‘3’ down the coast.

“All beach towns. They might have started this in an unusual location, perhaps hiding in plain side, in a closed hotel or restaurant, somewhere right in tourist country. Not a bad idea.”

Part 4

They waited for more updates from Spy, but the phone stayed quiet. When the room became too boring, and the view from the balcony too hot, they hung around a hidden terrasse in the back of the hotel to avoid chance encounters with other traders. The less rumor they stirred on Silom, the better. If it became known, that they bought fakes at tourist rates, their reputation would suffer. The gem trade was a village that way.

Three o’clock passed without an update. Strange because Mr. Spy always texted, almost obsessively, at times straining his client’s nerves. At five, against the rules, they called Spy’s mobile. Voice mail. More waiting.

From then on, they called every other hour, but the phone remained stubbornly off.

They watched movies, had room service, and went to bed with a dull sense of foreboding.

When no news had come the following morning, they started to worry seriously.

After lunch, they called Spy’s secretary. At first, the woman was all professional secrecy, but when Ed identified them as ‘the clients from Silom’, she talked a lot:

‘Yes, he is gone, since yesterday, but he didn’t call, and worst, did not return at night. Imagine! Not his way at all, and he doesn’t answer the phone, not even his emergency number. Nothing for 24 hours! Never happened before. I can’t call the police, can I? They hate us. What else can I do?’’

Etc. etc.

Ed could not get in a single sentence. In the end, they hung up on the lady to stop her from talking on.

In London, Peter was in conference but left a message that he trusted their judgement. They were to decide. While Peter had given his passion to gemstones, it was the price of copper that could sink his company, which in turn would shake the global mining market for weeks. A missing PI in Bangkok was not on his radar.

They decided to start searching themselves and set out to see Sandaporn. If the trader had returned from his trip to the Alexandrite facility but Spy had not, then things were getting complicated.

They had to wait a while but then were received with the usual professional courtesy.

“I have your trillion pair,” Sandaporn said in his office.

As the trader opened his safe, Ed checked for the coin. It was gone. Sandaporn had found their gadget. Ed tried to remain, or at least appear, unconcerned. But Lizzy stared at him. She sensed his worry right away. Sure, Sandaporn would notice, too. Or did he? He seemed friendly and relaxed. Yet, reading an old crook like Sandaporn was like night-walking a duck with blindfold. He might have given the coin to building-security and let them deal with it. Espionage was nothing new or uncommon on Silom. Few datapoints help more in negotiations than the other’s buying price, especially in the elastic valuation of gemstones. Or had Sandaporn already called the police? Was he trying to keep them in his office longer than usual? Would they be picked up by the police soon? Ed wanted to leave, quickly.

They bought the pair Alexandrite and took their leave. No police waited in the front office. Ed breathed lighter.

In the elevator, before Ed could speak, Lizzy said, “Did you see the draft brochure for a shrimp farm? On his desk?”

“The coin was gone.”

“I know. But the brochure, did you see? For a shrimp farm. The design was not finished, still with notes and corrections on it. A draft for a new business, something with ‘Novelty’ in the name.”

Ed stared at Lizzy, his brain too stressed to understand.

“Shrimp farming?” he asked irritated.

“Yes, shrimps, the nasty little stinkers.”

“What the heck would Sandaporn want with shrimp farming?”

Gems and shrimps were such opposite trades. Shrimps would start stinking during the time it may take to negotiate a single important gem. They were terrible to transport, never appreciated in value but ruin your health after a week, just opposite from gems. Did Sandaporn diversify? Ed didn’t think so. A gem trader in seafood was like a car racing company investing in used bicycles.

Then, Ed caught on, “They are pretending to farm shrimps!”

“Finally!” said Lizzy and boxed him on the shoulder. “I wanted to snatch the brochure, but it was too risky. I did memorize the town, though. Bang Soa Tong, or very similar.”

In silence, they hurried back to their room and checked the map again. Bang Sao Thong lay just north of Amphoe Bang Bo, ten kilometers from where Spy had last checked-in.

They looked at one another and nodded.

Ed said, “Let’s go. If we can’t find Spy, we can still see if somebody is faking gems there.”

“Yep, finding a gem factory amongst shrimp farms shouldn’t be difficult. We just need to search for something that’s not smelling.”

Lizzy loathed shrimps, or prawns, or any other ‘wet vultures’, even dead ones. Some childhood trauma.

They arranged to rent a most inconspicuous Toyota Camry and left Bangkok on a sixteen-lane highway to the South, traveling lightly with a joint backpack, taking only water, maps, their four phones, a few bundles of 500€ notes, a few thousand Baht in cash, Peter’s credit card, and their IDs.

After three hour’s drive they neared Amphoe Bang Soon, a small city with harbor and access to vast mangrove forests protecting Bangkok from floods, at least before they had been hacked off for shrimp farming.

They stopped at a little roadside lunch restaurant, and Ed ordered fried shrimps, while Lizzy stuck to a sandwich. Ed praised the food and interviewed the owner.

‘Yes-Yes, fresh-fresh from here. My brother-in-law’s farm. Yes, many-many farms. Big-small, old-new. No-No, gems not, why gems? Yes-Yes, a new farm just started, big-big. Lots of money. Name is, uh, Noveeltie, yes, Noveeltie Shrimp. Sure-Sure. Welcome.’

“That’s it!” Lizzy said as they started the car.

They searched the signs along the road for anything with ‘Novelty’ on it.

Soon, they found a small but shiny new sign, sticking out between dusty and rusted boards, reading, ‘Novelty Shrimps.’

They turned and followed the dirt road, passing by farm after farm, pond after pond, wooden signs, written in Thai, most with one hut towards the street, surrounded only by meager fences. Shrimp farms, by the very nature of their extended business, had little need for security. Nobody wanted to steal shrimps here.

After a few minutes, they slowed, staring ahead. To the right, off the road, next to a bamboo forest, stood a Camry, just like theirs, but burned-out and without number plates.

“Wait… was that?” Lizzy turned in the seat to look back. “Did Spy mention getting a rental?”

Ed continued driving, his hands gripping the wheel harder.

“Yes, he even gave me their number, recommended this company, where we got this one. You think that was Spy’s car?”

“I certainly hope not. Jesus, but that did look like a very recent fire. It was practically still smoldering,” Lizzy said in a low tone.

Ed kept driving.

“Do you think they would burn somebody’s car for sneaking up on their business?” Lizzy asked.

“I don’t know, but I think Peter would agree for us to stop here. What you say?”

Ed slowed down, searching for a place to turn the car but the road was not wide enough, barely allowing two cars at once. To the right bamboo forest continued, to the left, swamp molded into square blocks, each the size of a tennis court, and several feet deep.

“But we need proof,” Lizzy said.

“Take a photo of the wreck,” Ed said, then hesitated.

“He might have torched his car with a cigarette.”

He paused again. “Only Spy didn’t smoke.”

“No cigarette burns a car like that. I have seen my share of torched cars in Africa. Somebody poured gasoline into that one, and a lot, too,” said Lizzy. “No, Sir, that was not an accident.”

They followed the road, were forced to turn right after the bamboo forest, and stared at a very different type of building, twenty meters ahead. The road dead-ended in a massive gate set in high concrete walls, with only one small metal door on the side, crowned with Dannert wire and secured with cameras on poles pointing every way.

Ed hit the brakes.

“This looks more like a prison, or a drug lab,” Lizzy said.

“That’s it! We’re out of here,” Ed said, changed into reverse and turned, only to see a large water truck coming around the corner. The lorry closed the distance, stopped behind the Camry, and honked with a nasty blast. Left and right of the road now lay nothing but shrimp ponds.

Slowly, the gate opened inwards. The truck’s motor howled and inched forward until they stood bumper to bumper. HONK!

Ed cursed, changed into first gear, and slowly drove into the compound.

The gate closed behind. The truck had stayed outside.

“Oops!” said Lizzy.

Part 5

The compound consisted of two-story buildings set in a U-shape opening towards the gate. From one building several men rushed at the Camry, while a fat Indonesian-looking man, dressed in a sarong and a stained suit shirt, stood in a door, his piggish eyes watching them sharply. The eyes, though small and black, seemed to burn through the mirrored windshield and rested first on Ed, then on Lizzy.

Their central lock was still activated, and the motor was running. Ed considered to crash his way back and out. He remembered the lorry outside, and the swamps. Without four-wheel-drive he would not get past.

“Let’s play nice and innocent,” Lizzy said. “We done no wrong.”

Ed switched the motor off and released the door lock. Immediately two men opened the doors and motioned them to leave the car.

Ed made a slowly-slowly sign and reached for their rucksack. He exited the car, stretched, yawned, and looked around in tourist-fashion. Only then did he turn and took a few steps towards the fat guy in the door.

Lizzy had stepped from the car, too, and sided with Ed. Now, the fat man was staring her clothes off with a dreamy expression. She was used to onlookers undressing her but, eyes aside, this man was awful to behold. Thin hair lay plastered in half circles to hide the bold head with pimples between overly wide ears. Underneath, two hundred pounds bulged in a five-foot vase-shaped body. His default facial expression seemed sneering condescension. Gosh, this may be the ugliest man she had ever lain eyes on.

Thud!

Somebody had closed the car doors behind them.

Ed didn’t look back but sauntered towards Mr. Ugly. He waited for Lizzy, and together they walked up to the man, both folding their hands in a classic polite Thai Wai. The man didn’t Wai back but frowned, adding anger to the condescending sneer.

“Hello! We want to buy ‘New Mine’ Alexandrite,” Ed said, looking bravely into the man’s eyes, feeling a headache creeping into his temples.

“Hi there!” added Lizzy in a friendly tone.

The man didn’t react, didn’t move. No shaking hands. No smiles. Very Un-Thai.

“We don’t retail here. Or did you see a sign? Who send you?”

The man’s voice was the opposite of his outer appearance. Well-tuned, baritone but without scratchy darkness, slow, clear English without local accent.

“We don’t buy retail either, or we could have stayed on Silom,” Lizzy said.

Again, the man didn’t as much as blink. He simply ignored Lizzy as if nobody had spoken. He had seen his fill of the woman and now kept his eyes fixed on Ed. Women had no place in his business, especially not black ones. They were but pretty things to be exhibited, if occasion arose, but other than that they were not supposed to leave the house. Guarding children, cleaning and cooking was their job. If foreigners insisted to bring them in the office, they could not expect everybody else to talk to them, right?

For a while, Mr. Ugly just stood there, looking Ed up-and-down, contemplating. Then he came to some conclusion, nodding to himself with an unpleasant smile, muttering ‘In shaa Allah’ twice.

“Well, then that’s that, if you really want, come on in, as-salaam alaykum,” he said with his strangely accomplished voice, still smiling in his strange way, and turned back into the building.

They followed him up a staircase to the second floor. Other men came up behind.

The upper level consisted of a canteen to serve perhaps twenty men and a classic Asian chef-office at the end of the corridor. Mr. Ugly ushered them in, always smiling and sneering at the same time. From the top windows, one could see over endless fields of shrimp farms, the tapestry of global protein transformation.

Instead of shrimps, however, the office smelled of incense-sticks and rose-pedals, fragrant smoke wafted in the air, like in a cheap spa in Bangkok. A thick carpet lay on the floor but there was no AC. They had taken off their shoes outside the door.

Mr. Ugly plopped into a seat behind his desk, breathing heavily from the ascent, and pointed at two chairs, his eyes still fixed on Ed, further deepening the headache.

At the door, four men squeezed to get a better view. Mr. Ugly, in a less pretty voice, told them to bug-off in Bahasa Indonesia, followed by a curse.

With the door closed, and everybody seated, Mr. Ugly said, “I know your name, but you don’t need to know mine. I have been thinking what I would do if you came here. In fact, I had considered to come to Bangkok. But Masha’Allah, he decided for me. Here you are, and I have not much choice.”

Ed and Lizzy exchanged surprised glances.

“Yes, I know why you have come and what you want and everything else. Your investigator, that pretty guy in the strange suit, he came the other day. We don’t get many uninvited guests, which is how we like it. See, I have this.”

He pulled a ten-baht coin from his shirt pocket, twirled it through the air and caught it with surprising agility. “I know it all. Your man talked, dear, how he talked!”

“Where is he?” Lizzy asked.

Again, Mr. Ugly ignored her, keeping his attention on Ed.

“Did you burn his car?” Ed asked.

“Yes, but we took him out first,” Mr. Ugly smiled generously. “I needed to hear his story, after all.”

“The rental company will make you pay for it,” Ed said. “You’re crazy!”

“Don’t get agitated. As if I cared for a rental company. They’ll never find the car anyways.”

“Where is Mr. Spy?” Ed asked.

“Huh, really, that’s what you call him? Mr. Spy? How perfectly ridiculous!”

Mr. Ugly grinned into their frozen faces. He was amusing himself.

“I don’t believe you. He is a pro. He’d never talk,” Ed said, with some firmness in his voice.

Mr. Ugly went into an unpleasantly long belly laugh.

“Oh, no, Mr., huh, Spy talked, all right—” he finished with a snicker, then suddenly looked up with a deadly serious face.

“He was, not is, a pro, perhaps, but he talked, long before we fed him to the prawns, that was. By then, he had moved on to Jannah, luckily for him, I imagine. May Allah grant him mercy. He was brave, a true martyr, I must admit.”

Humor returned to Mr. Ugly’s face.

“But I do think shrimps prefer fresh meat, like alive. Not that I know much about it. Just an educated guess.”

For the first time since he had undressed her downstairs, Mr. Ugly looked at Lizzy.

“You two, they can have fresh, still twitching and all. Yes, I think they’d like that. Nicely bound in copper wire, not duct-tape, or they chew it up again, although, as I mentioned, your friend wasn’t moving anymore. One never ceases to learn. Can’t use duct-tape in such cases. I didn’t know shrimps would eat it, did you? Must be the glue. I guess they get high on it. They left nothing behind, not even the bones, last I checked, half an hour ago I did, some teeth perhaps. Of course, we had to undress him. I don’t think they’d eat a suit, especially not in such color.”

His eyes flickered. “No worry. First, we get rid of your clothes. His, we burned with the car, but the lab has an incinerator, so no problem.”

Ed looked straight at Lizzy. She blinked nervously and there was an unusual edge in her jaw. Her skin had turned greyish.

Could shrimps…? Was it possible to be killed by shrimps? Decidedly yes, it was possible. If one couldn’t move, they would take the eyes first. Their maws would do a slow job, ripping off little pieces, one by one but in a thousand places at the same time. No Spanish inquisitor could have wished for worse. How very nasty! A personalized vision of hell for Lizzy.

After enough time to imagine details had passed, Mr. Ugly added with a generous gesture, “Or shall we negotiate a deal?”

Lizzy looked at Ed with wide eyes.

“We are all deal,” said Ed, and, after short rummage, pulled the bundles of euros from the rucksack.

He waved them in the air. There may have been 25 or 30 thousand, but Mr. Ugly didn’t look impressed. He got up and without a word took the money from Ed’s hands.

“I’ll keep that for good luck,” he said smiling, and winked an eye at Ed. “Or in case I must pay the rental, which I doubt.”

“We also have a credit card, but then I need a machine. I think it’s good for the same amount if you stretch it over a few days. We can arrange that,” Ed said somewhat hastily.

Mr. Ugly raised his pudgy hands. “No, no need. A deal is all I want.”

“What is it?” Ed asked.

“I want to sell the treatment process to OneOre. The whole factory, in fact.“

“OneOre?” Ed fainted surprise. Mr. Spy had really talked.

“Yes, OneOre. You heard me right. Don’t play games. I know your story,” said Mr. Ugly and leaned back. “My treatment here creates an added-value of 2.4 million, annually.”

“Baht?” Ed asked.

“Don’t play, I said. Euros.”

“Why would OneOre want to make fake Alexandrite?” asked Lizzy.

The stare remained on Ed, who had to repeat the question.

“Why? It’s good business. With their sales channels, they can sell the lot for double, and, let’s not forget: I won’t feed you to the shrimps,” Mr. Ugly answered.

“You think OneOre wants to invest here in the swamps, just to rescue two silly foreigners?” Ed’s voice sounded less firm than he wished.

“Perhaps not OneOre, but Peter Pestana would.”

Not only had Mr. Spy talked, but he also had done serious research, for they had not mentioned their friendship with Peter.

“Uhm, so what’s your ask?” asked Ed, just to cover his despair and win some time.

“We estimate five years before the market collapses. So, that’s five times 2.4.”

“Twelve million dollars? You must be crazy. Even if Peter wanted to, his shareholders would fire him.”

“No-no, Euros, remember? It’s less than his entertainment account. No problem for a guy like him. He listed a net-worth of 3 billion or so. Can’t remember Euros or Dollars.”

A rock, and not a precious one, seemed to lodge in Ed’s stomach. “I don’t think so. It’s not OneOre’s business model and we are not Peter’s kids, only partners, and not very important ones, at that.” No firmness remained in his voice.

“Can you hear?” Mr. Ugly pretended to listen.

Ed shrugged and tried a smile.

“Hungry shrimps: ‘Food! Food!’”

He mimicked an animal with little antennas and broke out in another belly laugh.

Lizzy made a face as if she was going to throw-up.

Finally, Ed found some anger for his words. “It’s not business. It’s blackmail. Murder. You really want to screw with OneOre? From your stinking little compound here? Peter will hire a pack of nasty mercenaries and clear this shit hole. You are crazy. OneOre does business in worse countries than this. They are pros.”

“Yes, but he doesn’t know where to send his pros, now does he? Nobody knows. I take the money, give you the formula and the keys to this place with everything set up. I have a lab manager to run the process for you. OneOre can make a nice profit.”

“But how, how do you want to get away with this kind of money and–”

Mr. Ugly interrupted, “I’m happy we have entered negotiations.”

Ed ignored the remark. Negotiating was such a strong habit.

“You have to keep the formula to yourself, of course, no posting on the web, huh?” Mr. Ugly winked and smiled.

He really had done his homework. Ed considered other solutions. Escape. Violence. Threat. Nothing good.

Mr. Ugly seemed to have sensed the alternatives swirling through Ed’s mind. “Just in case you want to jump me, you would not get out alive. I have twenty loyal men outside, and they think they get their share. They’ll fight for it.”

Lizzy issued an angry growl – not a nice sound, but then Mr. Ugly had never seen her swing a squash-racket or drive an SUV.

“I have to call Peter,” said Ed and motioned to the ancient phone with a turntable that sat on the desk.

“Shush, no, no, not on a landline. Your Peter can track us here. Nope. Won’t do. That would be stupid.”

“Then a mobile.”

“No. Can be tracked too, but anyways we have no reception here. You will send a fax. But from Bangkok. You’ll order your hotel to do it. The Lebua, right?”

Ed sighed. The man had thought this through, and he wasn’t stupid.

Mr. Ugly sat smiling, sneering, staring.

“Stop looking at me like that, or I’ll die of a headache before you can sell us,” Ed said and rubbed a spot on his forehead.

Mr. Ugly averted his eyes and pushed a paper over the table.

Ed read the precise schoolbook script:

‘Alexandrite factory for sale. 12 million euro. Without deal, Wild Monkey loses management. Urgent. Call 66 60 87 687 87.’

“He will understand, don’t you think?” asked Mr. Ugly. “I have a man in Bangkok. He will negotiate for us, for you that is. Nobody will ever know where you are.”

Mr. Ugly picked up the ancient phone standing on his desk. “What was your room number at the Lebua? 552?”

Part 6

In London, Peter Pestana, sat over the Financial Times with a glass of freshly pressed orange juice. Frank, his personal assistant, a new hire from Germany, entered the private suite and handed him a sheet of paper.

Peter leaned into the sofa, took the paper, and murmured with a smile, “Ah, we still have fax machines.”

His smile dried up, as he stared at the two lines. He checked the sender code. He read the text aloud, checked the header, again the code, looked out of the window for a while, sighed, and picked up the phone on the sideboard.

Logan Jullse, the security chief, knocked on the door three minutes later. Logan was a generation younger than Peter, red haired and with the nose of a drinker, although he never touched alcohol.

“L, we have a blackmail situation,” Peter said.

“Who is blackmailed?”

“OneOre. Me. Never-mind. They seem to have two of our, huh, agents.”

“Agents?”

“Yes, I hired them to find a treating facility.”

“Treating?”

“Chrysoberyl into Alexandrite.”

Logan opened his mouth, but Peter stopped him, “Just listen, will you? I hired this couple to locate a factory in Thailand. That’s all you need to know.”

Logan shifted in place, but kept his lips pressed together.

“And, no,” Peter added with a sigh. “We do not have any more operation in Thailand before you ask. That’s why I hired outsiders, privately, sort of, but we must deal with it. Do you still have your contacts in Bangkok?”

Logan only nodded but allowed himself a questioning glance.

“Twelve million,” Peter stated.

Logan clicked his tongue and waited.

“Euros, that is. Twelve for two of my friends.”

Logan broke his silence, “Sir, the board will never allow to spend six per person.”

“My board won’t allow anything. Especially not via the purchase of a half-illegal treatment facility in Thailand. Even if I could push it through the board, it would need months of due diligence and paperwork. No, we need to do this quick and, uh, creatively. Officially, OneOre cannot be involved. This was all based on a handshake. But I value my handshakes.”

Peter got up.

“We are going on a holiday to Thailand. Take two experienced men with local experience. We leave at 14.00.”

Later in the afternoon, Peter’s private jet crossed the British channel with five passengers. Logan and two of his men, Rob, a short sturdy Brazilian and Jesse, a fluent Thai-speaker with lush brown hair, read and re-read the fax, studied a map of Bangkok and the floor plan of the Lebua.

Peter told young Frank how he had met Ed and Lizzy in Madagascar, and why their company was connected to a monkey named Siegfried.

After an early dinner on board, the men joined to develop hostage scenarios. Later, well past midnight in Bangkok, Frank and Peter napped in the back of the plane. Logan and his men didn’t sleep but continued what-if games. As the sun rose over the dark horizon, Logan had burned the situation down to three main options, none included any shrimp farming.

Peter awoke as the jet descended to Don Muang Airport. Bangkok’s street vendors had prepared fresh Tom Yang for the day, traffic had filled the streets, and soaked the air with smog. After the brief controls for private jets, the group checked into the Lebua State Towers. Frank had booked the complete top floor. The elevator was programmed to stop on their floor only with a valid key card and a code.

At first, Logan bribed the hotel manager and a cleaning maid to access Ed’s and Lizzy’s room. He found it deserted in a haste, but without useful clues except for the reservation of a rental. The company confirmed the car being a day overdue, and agreed, after some threats and assurances, to provide its number plates, color and make. However, they had no way to track the car, no GPS signal, no records of highway tolls or petrol fillings. If the car was not returned within the next 18 hours, they would automatically report it missing with the authorities. Logan got the rental manager to postpone the police report for 48 hours.

Meanwhile, Logan’s men interviewed hotel employees, guests or anybody willing to talk around the Lebua. They confirmed the couple had been in and out of the hotel, but nobody had seen them the previous day.

After they had reported their findings, Peter and Frank stayed behind to begin negotiations. Logan went to visit an old contact in the telecom ministry, while Jesse and Rob went out to ask for Alexandrite on Silom, and perhaps find somebody who knew Ed and Lizzy.

Part 6

To the south, the couple had slept on mattresses in a locked cellar room with only an AC, no chairs, no table. For breakfast, as for dinner, they had managed to swallow some dry rice rescued from under the too spicy sauce. The night had been unpleasant, either too cold when the AC ran or too hot before it started up again.

Their guards, two silent Indonesians, were stationed outside their door. Neither looked bribable. In any case, Mr. Ugly had confiscated all their belongings, leaving them nothing to bribe anybody with. He had even taken Lizzy’s jewelry which made her so angry that Ed was afraid she would start a fight, but luckily, she had refrained from doing so.

Ed banged on the door to go to the restrooms. He was escorted up the stairs and down two corridors. They passed a room that reminded him of a pharmaceutical production, large chrome structures, with tanks, pipes, and regulators, and something like monitors. When he stopped, the guard politely ushered him on. They came to a room with a row of WCs, each inhabited by several hundred flies, but no stalls. Three wash basins, according to the yellow stains all around, doubled as pissoir. They probably shower outside, in open air, Ed thought. He would demand a shower, later, and scout some more. The complex was far larger than it had appeared from the yard. He could hardly tell in which direction the exit lay.

When he returned, Lizzy had set her mattress against the wall and was punching and kicking it with furious grunts.

She stopped and stared at the guard.

“Don’t,” Ed said, and the man understood, hastening to lock the door behind.

“Don’t what?” Lizzy asked sharply.

“Don’t use the wash basins.”

Part 7

In Bangkok, Peter dialed the number given in the fax. It rang only once and was answered with a curt, “Sawasdee-krap?”

Peter confirmed that he had the right number by asking, “How do you expect us to deliver twelve million in cash?”

The man didn’t miss a beat, but answered with professional calm, “My client is reasonable. Only two million need to be in cash. The rest can be in OneOre bearer shares, or gold, for example.”

Frank, listening in, rolled his blue eyes.

“We can work on that. But even two million in cash is a load of paper,” Peter said.

“Not too bad, four thousand 500-Euro notes will do fine. All you need is a rental car which you drive to a reserved parking space. We take it from there.”

“I’m to fill a rental with money and then leave the key? In Bangkok?” Peter asked.

“Basically, yes. But these are details we will partake later. Be sure, we take good care of the retrieval.”

“Look, I need–”

“Assurances obviously. Yes. You will see a recent video with the couple in good health. When you get your friends back, they will have the documents of sale, describing the chemical process involved. They will also have the location and security codes of the factory. You can take it over in working order, including staff.”

“Very kind,” Peter smiled sourly.

“Thank you. How long will you need?” the man asked.

“I have to get back to you.”

“Fine. I will call this number again in twenty-four hours from now. Is that to your liking?”

“My what?” Peter frowned. “Look, I call you when we have–”

“No. This phone will not be in service. I will call you.”

The line went dead. Peter sank into a sofa. After a sigh, he said, “I do have some emergency funds on the plane. Cash, bullions, and a collection of Burmese rubies.”

“You are planning to pay these people?” Frank asked.

Peter stared at his hands, nodding slowly, muttering, “If I have to.”

Soon after, Rob returned with an Alexandrite and Peter confirmed it to be a treated Chrysoberyl simply based on size and perfection.

Then, Logan came from the Telecom ministry.

“That number, in the fax, is a recent registration. Only a few calls made, all from inside the JTC,” he said.

“No good in a building with 4000 people. Who is the owner?” Peter asked with little hope.

“An anonymous sim-card provider,” Logan answered.

“Huh, they are not stupid,” Frank said with respect.

“Wait!” Logan held up his hand. “I also got a received-call list from the hotel reception. All incoming numbers and their calls in the three hours before the fax was sent to London.” He laid a USB stick on the table. “2334 calls from 645 numbers. The hotel phone system does not accept callers without ID. The number you got in the fax is not amongst them, I checked right away.”

Peter took the stick and nodded.

“Good work,” he said to Logan, then he turned to Frank.

“Please return to the jet and get what is in its safe. I will instruct the pilot accordingly. Take a car and driver from the hotel, no taxi.”

Frank made a ‘no-need-to-tell-me’ face and left.

The men downloaded the call logs onto their computers and began sorting them by caller ID, length, and frequency. The Lebua’s laundry, airlines, travel agencies and obvious suppliers eliminated 177 numbers. Connections to guests made 88 calls. Employees and staff family threw out another 87. There were 55 miscalls or interrupted connections of less than three seconds and 97 numbers who had called two or more times.

This left them with 141 numbers.

Peter made twenty test calls, ordering Logan, who played the hotel clerk, to send the exact fax he had received in London and book it onto a room. The calls came out with 80 seconds on average, with the shortest being 55 seconds, and the longest one hundred. Listing the remaining numbers according to length of call, there were 18 numbers left within 55 to 100 seconds.

These 18 numbers were selected for closer investigation. Each man took six numbers and researched their details in Logan’s data, on the web and on the OneOre servers. Only if they couldn’t get enough information, did they call the numbers and spun stories to find out who was behind the call to the hotel. There were five escort girls or lady-boys, one couldn’t tell which from the voices, a health inspector, a school, two European businessmen, one dentist, a crocodile farm, a monk, a street vendor, and a gay bartender. In the end, they had eliminated all but three callers whom they could not make sense off, or which sounded suspicious. One was a construction-side near Silom where their call was answered only with Russian curses. A venture fund with the name ‘Happy Interest’ from Bangkok refused to reveal any information. At the third, a shrimp farm in Amphoe Bang Soon, south of Bangkok, nobody answered the phone and there was not a shred of public data available. The company had been registered only a month earlier.

Peter ordered a shrimp cocktail to the room and then paid the waiter to get the Chef. He inquired about the source of these ‘very good’ shrimps. Upon hearing that they came from Uruguay and were in fact prawns, he asked the Chef if he ever used any Thai shrimp.

The Chef wrinkled his nose. “Thai shrimps stink. Never, Sir.”

“Have you gotten any local offers recently?”

“No, no. Different business altogether. These shrimps are used only for fish paste, powder, and sauce, or crackers and such,” said the Chef.

Peter dismissed him with a reservation in his restaurant for later in the evening.

Rob, calling other VCs in Bangkok, was told that ‘Happy Interest’ planned on setting up a tourism fund next year. They had probably called for information and been rebuffed but wanted nobody to know.

Frank, who had returned from the plane with three golden Halliburton suitcases, suggested to go and see the construction side.

“I’ll go. I speak Russian,” said Rob.

Logan nodded, and Rob left.

Little later, Jesse returned from his Alexandrite hunt.

“I have found a Thai who said he can bring me to the main distributor of these new Alexandrite. And, lucky daisy, he mentioned that he done very good business with Farangs just the other day. They bought from him and then went to buy from his source. That may be them, no?”

“What’s a Farang?” Peter asked.

“Farang means ‘potato’, a Thai byword for foreigners, as in ‘round, soft, white,” Jesse said.

“Charming description!” laughed Peter.

“Anyways, he will introduce us to the source tomorrow. We meet him at 09.45,” Jesse finished.

“Great job, Jesse,” Peter said, and held up his hand. They stood and waited for him to speak again.

“Let’s visit this seller tomorrow. If he recognizes me, if he reacts strange or shows any weird behavior, we can’t leave him there. L., in that case, I want you to bring him down, right there. If need be, we take over his office by force. Bring the gun. We must play it flexible. If he doesn’t know me, if he doesn’t blink at all, then, we simply buy Alexandrite and that’s it. Jesse, you will play the local schlepper. Me and Logan, we’ll be there for quality check of goods. Rob comes for security in case things get heated. Frank, you stay here. If the guy is clean, we text you his details and you move all levers to find out more. We need to know where he lives, what his connections are, who are his friends, anything helpful. OKI?”

He looked around, all nods. “Then to dinner!”

Later, Rob returned from the construction side. He looked disheveled and had ripped one sleeve.

“I had to run and hide. Almost got caught. The place teams with illegal workers, that’s why they didn’t like me sneaking around, but it’s in phase one. No building useful for a kidnapping, or a secret factory. Russian mafia for sure, but nothing for us.”

Part 8

The next day, at 10.20, the group, led by the Thai dealer, filled Sandaporn’s front office.

Without appointment, the assistant was reluctant to admit such a crowd to her boss.

Hearing the commotion, Sandaporn came from his office. Peter stepped up and showed him the golden Halliburton he carried, and he was all salesman, ushering them into his inner sanctum with humble curtesy. No sign of distress.

Peter motioned Logan to sit with him and study trays with gems, while Jesse occupied Sandaporn with much talk, and Rob texted the location and name of the company to Frank who started to research on the trader and his dealings. After leaving almost one hundred thousand euros in cash at Sandaporn’s office, they asked for a new appointment.

“At your pleasure. Come any time. I’m here from ten o’clock on, sharp, every day,” said Sandaporn with pride.

When they arrived back at the Lebua, Frank awaited them with news. Sandaporn had broad holdings in various gem and jewelry businesses but none in perishable goods, except for ‘Novelty Shrimps’, a very recent investment one hundred kilometers to the south of Bangkok.

“Bingo!” said Peter and leaned back in his chair. “But how is it that this guy doesn’t know a thing? He didn’t recognize me, right?”

“Yeah, no, he did not,” Logan agreed. “He was straight, flawless. Once he saw the Halliburton, he was all business.”

“Then, there must be another level. They must be at the factory, and the deal is done from there. Sandaporn doesn’t know,” Peter said.

“Well, let’s go there. Let’s go to… what was it? Ang Bang Soup?” Logan said.

“Amphoe Bang Soon,” corrected Jesse in the precise pronunciation only a Thai connoisseur could deliver.

Peter made a ‘slow-down’ motion and looked at Logan.

“We don’t want to rush it now. Nothing will happen as long as they wait for money. L., I would like Sandaporn to come with us. We can’t tell him about this blackmail thing, yet, it would get too complicated, but I don’t want him running free when we visit his investment and kick-in doors. We better keep him close. He will not want to come without explanation, but I’m sure you can convince him otherwise, right?”

Logan considered for a moment. “Yes, he said ‘sharp at ten’. That means he is using the BTS to go to work. We–”

“I do not need to know,” Peter interrupted.

Logan closed his mouth and nodded.

“Frank, we need two good cars, real cars. At least one must have tinted windows. Once Sandaporn has accepted Logan’s kind invitation, I would like to leave for the south right away.”

Peter turned back to Logan. “Is tomorrow morning enough time for you to get Sandaporn into a car?”

“Sure. I’ll have Sangaporn all happy to join us and nobody will know about the location or miss him.”

“Sandaporn,” Jesse corrected.

“Do you need more men?” Peter asked Logan.

“There is one who could help. His name is Getawajapot. He was police chief for Bangkok, now retired. For a thousand euro a day, he will be happy to help, if I explain him the good reasons. He will not do illegal stuff, but he understands the risks if foreigners are held for ransom in his country. That man can move mountains here.”

“Sounds promising. Please hire him. Frank, let’s have three cars then.”

“No need,” said Logan. “If Getawajapot comes, he will bring his own car, and driver.”

The next morning, Mr. Sandaporn arrived with the usual ten o’clock train and walked to the JTC. Floating in throngs of laughing office girls, traders, designers, and goldsmiths, he noted two men settling left and right. Both foreigners, one tall and the other short, looked strangely familiar. Before he could make the connection, the one with long brown hair said in fluent Thai, “Please come with us and be ever so natural about it.”

The other man took him gently by the elbow and with little pressure caused a nasty pain shooting into his shoulders. Sandaporn winced but walked on, even as black spots danced before his eyes. As soon as Sandaporn had swung away from the JTC, the pressure on his elbow subsided but the hand remained. They entered the Lebua’s lobby without any further incidences. But when Sandaporn realized, they were heading to the underground garage, he squirmed and protested. Rob renewed his pressure on the elbow, while Jesse talked to him in calm Thai. Reluctantly, he followed and, after padding him down, taking his briefcase, phone, and keys, they made him sit in the back of a black Landcruiser with tinted windows.

Logan was already waiting in the car.

When Sandaporn saw that he was not to be murdered right away, he took a few deep breaths and calmed his blood pressure.

Logan said, “You need to call your secretary. Tell her to cancel all appointments and that you go abroad for a few days.”

He handed Sandaporn his phone.

“Abroad? But she has not booked any flights.” Sandaporn squirmed, refusing to touch his phone.

“Then let her make a booking, say to Singapore. Plus hotel. And ask her not to tell anybody.”

Logan pointed at Jesse who had entered in the front. “He’ll be listening, and you know he speaks excellent Thai, so please be brief, normal and just talk about necessary items.”

Rob reached for Sandaporn’s elbow, but he flinched away.

“No need. I understood. Don’t worry.” He took his phone from Logan.

Jesse listened to the call, concentrating with both eyes closed, one hand lifted and ready to signal Rob to cut the line. The conversation went smoothly and uninterrupted.

When Sandaporn disconnected the phone and returned it to Logan, Jesse exited the car and politely offered his front seat to a tiny, old gentleman who climbed with a routine motion into the high car.

Mr. Getawajapot, the bespectacled ex-chief, barely filled half of his seat. He looked like a child allowed to sit in the front. But a scar over the left eye attested to the brutal life he had lived in the metropolitan police. His intense personality quickly filled the car without a spoken word.

He turned to Sandaporn, joining his palms under the chin, and bowed his head in a Wai.

Sandaporn stared back with open mouth, almost forgetting his manners but then Wai-ed back, twice, bending far deeper and thus expressing his submission and respect for the older man, his eyes wide with surprise, and then fear. Getawajapot turned and looked to the front without a word, his blunt silence a social afront, showing strong displeasure, almost anger and scaring Sandaporn even more.

Unbound from institutional restriction, and well connected, Getawajapot represented the elite of Bangkok, a few dozen families who ruled a city of fifteen million with iron hands.

Another man, a tall Thai with impressive shoulders entered the car without greeting anybody and started the motor.

‘His driver, and bodyguard,’ thought Sandaporn and looked from the driver to the police chief, and around the interior. ‘His car!’

He remembered seeing the old man on TV during his retirement ceremony, shaking hands with Bhumibol Adulyadej, the revered King of Thailand, an ultimate honor for any mortal Thai. Angering such a man was almost like angering the King himself, or the gods. Sandaporn swallowed dry. He wished he had skipped office that day. These foreigners, whoever they were and whatever they wanted, had terribly good connections. Getawajapot did not join somebody for crime, not for the illegal. They wanted something the old chief could wrap his good conscience around. Sandaporn thought himself a legitimate businessman, not a criminal. His latest investment in the South was not-so-official but what had the police to do with gem-treatments? Nothing. Undisclosed treatments were frowned upon, but hardly a crime. After all, many Thais had made fortunes with gem treatments for decades. That could not be it. Yet, as they left the garage southwards, Sandaporn could not think of any other reason than his new treatment plant. His unease deepened. Something was going on. With Getawajapot on board, the foreigners could not be the criminals. If it wasn’t them, then who? The only possible answer shilled his blood. It was him. What had he done wrong? He recalled the previous days. The only excitement had been that ten-baht coin, which his weekly sweeper had found. He had shown the coin to the Indonesian running the facility simply to demonstrate how very careful they had to be, and then forgot about it. Dozens of buyers were coming every day asking for his ‘New Mine’ Alexandrite. They all desperately wanted to find his source, his secret. He had not suspected the two Farangs, but rather the unpleasant Han Chinese who had come later that day. These Hongkongers always tried to snoop out their newest treatments and take them back home. But no, now it was clear. That Farang couple had been sent to find him and his factory. The coin had been theirs. But still, this made no sense. There was something else. Two more cars belonged to their group. One Benz limousine and one of the new BMW crossovers. A serious show of force. Getawajapot would not get mixed up in a banal issue like gem treatments. And how had they caught-on his working routine so fast? He had seen them for the first time yesterday, but not 24 hours later, they had been waiting for him at the BTS. What on earth did they want with him?

He overcame his fear and asked polite questions into the car, without directing them at Getawajapot. Nobody answered. After the fourth question, the short man made a show to look at his elbow, and he stopped asking.

Part 9

Ed and Lizzy spent an anxious yet utterly boring day in their little room. All ideas to change their situation ran afoul the fact that they had no contact to the outside world, nor did they see any chance to escape. The steel door was bolted from the outside. The room was windowless, or if there ever had been one, it had been walled over. Twice they demanded an audience to get some movement or information, but no, ‘the boss didn’t want to see them.’

Lizzy had fluctuated between resignation and mad anger, released against her mattress. For lunch, they had been given fried prawns, as if to make a point. Lizzy had thrown the plate against the wall.

“That doesn’t help,” Ed said, looking at the mess.

“We attack that fellow when he brings dinner, take him hostage and get this ugly fuck to let us out,” Lizzy suggested with clenched fists.

“Ah, you think he cares about one man? No, no dice.”

“But at least, we could do something.” Lizzy punched her mattress again.

Later, before dinner, two men entered and bound Ed’s hands on his back and his feet so that he could walk only in small steps. Lizzy, they left untouched. Mr. Ugly would have been safer to bind Lizzy and leave Ed free. But what did he know about the wrath and revenge of a strong African woman?

When they entered the office, Mr. Ugly sat behind his desk and smiled ever so contentedly.

“I have excellent news. Mr. Pestana has come to Bangkok, and he is negotiating. We need to make a video of you two sweeties being happy and well. Perhaps the deal goes through today. If you are lucky, and if all goes well, you’re free in two days, and I can finally leave this stinking swamp. Allah, may he be praised, knows I’m sick of it.”

As before, the office wafted with strong aromas, incense sticks burned in all corners and in front of a little shrine at the wall. A slowly turning fan swirled the scents into an agreeable mix.

Mr. Ugly began a proud monologue about his successful venture while fussing over an old video cam.

“What about your business partner, your boss in Bangkok? Mr. Sandaporn, what does he say to you kidnapping people and selling his factory?” Ed asked.

“Boss? Ugh, boss indeed! That old fart has no clue. Thais! All stupid. I will be gone before he scratches his nose. Then he has no choice but deal with OneOre.”

Ed sighed and hobbled to the window. Shrimp farms stretched into the horizon. The afternoon sun glimmered on the shallow waters. Far behind thousands of little swamps, the Lebua awaited them with showers and clean bedsheets. The hands bound to his back felt numb and cold with the reduced blood circulation. Restricted in his leg movements, he felt helpless and silly, vulnerable and without balance. Mr. Ugly continued praising his own cleverness. Ed disconnected from the voice and recalled the dinner at the Elephant. He turned to catch Lizzy’s eyes, but she sat where she had been told to sit, on a chair a few paces from the desk, staring at the old fan churning in one corner.

With a flash, Ed knew what Lizzy would do and feared it, even as he was sick of his own helplessness and would welcome a solution, any solution.

They were alone in the office. Mr. Ugly had dismissed his men, not fearing a bound captive or this woman of a lower human class. Lizzy’s eyes glowed with anger and stored energy.

Ed said something like ‘look-here, we need to talk’ and, as quick as his bound legs allowed, hopped towards the desk. Mr. Ugly sat up surprised at the sudden movement, turning to Ed and taking his attention from Lizzy.

In the corner of his eyes, Ed saw Lizzy rise from her chair. With two long steps, she crossed the room and grabbed the fan by its thick stand like a two-handed ax, leaning backwards as she swung the fan with outstretched arms like a discus thrower, whirling towards the desk, combining natural elegance with the ability to plot motion in three-dimensional space faster than any computer. No sound came from her lips, her face was pure concentration as she put all her loathing against condescending men into the swing, her muscles trained in Kenya’s national squash team. She had played on number one for years and could have gone international, but such a career would have been short sighted. Nobody withstood the rigors of the fastest sport professionally beyond the age of thirty. Burning two thousand calories per hour, excelled only by skiing uphill, a good game could last two hours, and a competition ran over four games, eight hours of extreme speed and maximum force combined with outstanding spatial coordination.

The fan’s plug ripped from the wall socket, depriving the blades of rotating power. The cable whirled around the turning Lizzy as the fan’s rotor crashed into Mr. Ugly with the speed of a volley cross-court. The fan smacked him straight off his seat and his short legs came up as the chair overturned. Lizzy’s after-swing would have made Tiger Woods proud. For an instant, Ed feared for Mr. Ugly’s life, but nobody could stop Lizzy once she had come up to speed. She released her weapon, or what was left of it, and jumped over the table to strangle the man on the floor with both hands. Only then did she allow herself an angry growl.

Ed hopped around the desk, almost stumbling. With hands bound on his back he tried clumsily to pull Lizzy away but, in her fury, she shoved him aside. He fell on his back and for a moment rolled like a beetle.

When he finally got on his knees, Lizzy had a letter opener in one hand while still choking the man with the other, pressing him down with one foot on the big belly.

“Lizzy, enough, enough,” Ed pleaded, standing up.

The door crashed open. Two men rushed in. When they saw their boss lying on the floor, blood flowing from a broken nose and gashes in his face, they shouted for help.

“Close. Out! Close the door from outside,” Lizzy commanded and set the knife on Mr. Ugly’s neck. Confused, the men retreated out the door, but didn’t close it.

Lizzy started to kick the man on the floor. Luckily her bare feet and the not so well-trained kicking-routine did less harm.

“Lizzy, stop!” Ed said again.

Lizzy held the next kick, one foot in the air. “What?”

“He had enough. You got him. But we need him alive.”

Lizzy ended the kick halfhearted, her chest moving slow but strong. Ed motioned to a scissor lying on the table and Lizzy cut the tape on his legs and wrists, all the while keeping the letter opener pointed at Mr. Ugly’s neck, who made croaking sounds and tried to roll away but couldn’t get his body weight around before Lizzy again put her foot on his belly.

Outside the door, men were shouting, probably encouraging one another to storm the office but none dared.

They heaved the groaning man onto his knees. Lizzy pulled the cable from the wrecked fan. She did not bind Mr. Ugly’s hands but made a simple noose, flung it over his head and pulled the nod tight until the man gurgled and choked.

“Enough!“ said Ed.

Lizzy stopped pulling and pressed the letter opener into a bulge in the double chin, looking to the door, where three men dithered in panic.

“Close the door. Piss off!” Ed said to them.

Lizzy began to laugh. A wild, crazy sound, releasing leftover energy and tension. The men pulled back in fright, but still didn’t close the door.

“Tell them!” Lizzy said and underlined her request with a short pull on the cable.

Mr. Ugly croaked something in Thai or Bahasa Indonesia, and the men closed the door.

Lizzy looked at Ed for the broader strategy, her strength in spontaneous action, rather than planning. Ed picked up the phone.

“OK, let’s get Peter. If he is in Bangkok, he’ll get us out of here.”

He started to dialed Peter’s private sat phone number from memory but then realized the line out was dead. Either Mr. Ugly’s men had reacted extraordinarily fast and cut them off, or the Thai telecom was out of order. Ed suspected the latter in a rural area.

“Oh, did you not pay the telco bill?” Lizzy asked and poked Mr. Ugly with the letter opener. “This was working the other day.”

Mr. Ugly squeaked, then huffed through clenched teeth and bloody lips, “We are cut off half the time.”

His voice had lost its pleasing character.

“Look, if we can’t call for help, we need to take you for a road trip. You’re not going to like it. I can tell you now,” Ed said, and Lizzy smiled.

“Wait till the phone is back. An hour or two, max,” Mr. Ugly whimpered.

“No, we are tired of waiting. You walk with us.” Lizzy pulled the man up by the cable. “Tell your men to clear the way to our car.”

“Your car?”

“Yes. Our car. Any problem?” Ed asked.

“We burned it,” Mr. Ugly said almost with regret.

“You didn’t!” said Lizzy and pulled on the cable.

Mr. Ugly nodded, looking at Ed with a plea for mercy in his eyes.

“Stop staring at me, I told you already. If I get a headache, you get a blindfold. Anyhow, then we will take your car.”

The man waggled his head. “My car, I send to collect Chrysoberyl.”

“Then anybody’s car, for fuck sake, some car,” Lizzy snarled. “Don’t tell me you have no car here at all. If we don’t have a ride and no telephone, we go on a hike, like in walking on your short ugly legs.”

Mr Ugly spit what looked like a half tooth onto the floor. “We have only motor bikes.”

“No, that won’t do. Get the water truck ready,” Ed said.

“The water-truck? You want to drive the water-truck?” Mr. Ugly said with genuine surprise.

“Why? You think I can’t drive a truck?” Ed asked and took the cable from Lizzy’s hand.

They pulled Mr. Ugly up. Lizzy wrenched the man’s arm on his back, pressing the letter opener into his neck.

“Let’s go,” Ed said and pulled on the cable.

Mr. Ugly in the middle, they stopped two meters from the closed door.

“Tell them to open and step away. Get the keys. Keep distance and stuff,” Ed said.

Lizzy added, “If anything bad happens to us, I’ll make sure you join, got it? Nobody takes me alive.”

She looked over to Ed to make sure he got her point.

“Understood? Not alive.” She stabbed the letter opener deeper into the fat until Mr. Ugly squeaked, nodded.

“Call them,” Ed said and repeated the instructions.

Mr. Ugly cleared his throat with a bubbling cough and raised his voice to carry through the door.

A few fearful shouts and questions came from the other side, but the door didn’t open.

Mr. Ugly shouted again.

“The instructions. You remember? Distance?” Ed said.

Mr. Ugly resumed shouting.

Finally, the door opened and one of their guards peaked around the corner, beckoning them to come.

They moved through the corridor, men withdrawing in front and following behind, keeping the commanded distance but always threatening close. Ed, in front of Mr. Ugly, now walked backwards, holding the cable tight, constantly checking for the men behind. Lizzy, who could not turn and had both hands occupied, one locking Mr. Ugly’s arm between his shoulder blades and the other pressing the knife at the man’s throat, risked a determined grab from behind. Yet, the individuals lacked resolve, and the group leadership.

On the stairs, Ed feared that a quick shove would send them tumbling downwards in a heap. But nobody made a move, even as the couple had a hard time keeping their balance and control over their hostage while wobbling down step-by-step. Mr. Ugly himself may have jumped down the stairs and gravity would have opened their formation. But he was in pain and dazed, probably fearing a broken arm, or a dislocated shoulder, not to mention Lizzy’s punishment should he fail in his attempt. Thus, they managed to descend the stairs without attack and down another corridor to the main door.

There they were stopped.

A half dozen men, armed with determined faces, screwdrivers, and wrenches blocked the exit. The group was led by a thin grey man in a clean white coat, obviously the lab manager. Here was leadership. Perhaps, the others hadn’t attacked on the stairs because they knew this was coming. The man even had a name, or something stitched on his chest, his face was haggard, and his skin looked as if it had not been under the sun for a long while. He was holding a fire extinguisher in both hands, but had not removed the tube, wielding the tank more as a battering ram. Either he mistrusted it functioning, or he hadn’t thought of the disabling blast of powder he could unleash with it.

When Mr. Ugly saw the thin man baring the exit, he hissed, not relieved but angry, then cursed.

The lab manager shouted in a mix of Thai and Bahasa Indonesia, including the words ‘Farang’ and ‘Dollars’ followed by a number. All around the men shifted on their feet, securing their stances, readying for a fight. Judging from Mr. Ugly’s reaction they had decided to sacrifice their boss and pull through without him.

“It seems your men are not so loyal, after all,” said Lizzy and, with a quick controlled motion, poked the shoulder, not deep, but in the place where the tension must have been strongest. The shoulder made a wet sound that send a shudder through the group. Mr. Ugly squealed terribly through his severely tightened throat. Lizzy returned the knife to the double chin.

“Can you get them under control?” Lizzy asked.

Mr. Ugly began to talk, ever so fast, a waterfall of words, mixed with sobs and cries. They heard ‘formula’, and ‘OneOre’ and ’Pestana’ and more dollar amounts, and ‘Lebua’ and again ‘OneOre’ and ‘formula’.

The thin man seemed taken aback and the group began to argue fiercely. Mr. Ugly must have told them details they were not aware off. The thin man tried to shout them down but failed. Emotions rose, men yelling into faces, waving weapons. Some began pushing each other and it looked like a general brawl would follow.

Ed encouraged Mr. Ugly with a shove to defend himself some more. Again, the bleeding man talked, even faster than before, now with angry questions and curses directed at the thin man. They stopped fighting amongst one another and listened. Under the staccato of arguments, even the thin man looked hesitant.

“Get them to move and give us the keys to the truck! Last chance,” Lizzy said.

Mr. Ugly turned authoritative, screamed furious commands at his men, pinkish foam at the mouth. The rebellion broke. The thin man dropped the fire extinguisher with a disgusted grunt, folded his arms and leaned against the wall.

The others exchanged hushed words. Finally, they pushed a little boy forward, dressed only in underpants. The boy quivered in fear, holding out a worn MAN key. Somebody opened the main door. Bright sunlight crashed into the corridor.

Ed took the key from the boy’s shaking hand and tried to reassure the kid with a smile, but he only ran away with a little shriek.

The ex-rebels moved off through the exit and into the open. Only the lab manager remained behind, leaning against the wall with a grim face. Warm air, saturated with shrimp scent, rushed through the door. Still, it felt fresh and alpine in comparison. Only now, did they realize how oppressing the atmosphere in the corridor had been.

When they moved past the thin man, Mr. Ugly spat a gush of blood and saliva on the man’s white coat and hissed. For a moment it looked as if the lab manager would participate in strangling the boss, but Ed quickly pulled him through the door.

Squinting into the bright sun, they saw the battered water truck, parked with the passenger seat to the wall, nose to the gate.

“Shall I go and start it?” Lizzy asked.

“No, better stay together.”

They carefully crossed the yard, thirty meters perhaps. The ground was muddy from a nightly rain. Lizzy slipped once on her bare feet but recovered with cat-like balance and without further cutting the whimpering Mr. Ugly who clutched at his punctured shoulder.

At the lorry, Ed opened the creaking driver’s door. The circle of men had followed but they now seemed utterly discouraged and kept well out of Lizzy’s striking distance.

“I drive. We must be quick now,” Ed said.

Lizzy let go of Mr. Ugly’s arm and took the cable from Ed.

Ed counted, “One, two, three.”

They climbed into the cabin, first Lizzy, squeezing over the driver’s seat and pulling Mr. Ugly behind. Under a relentless sun, the lorry had heated to sauna level, smelling of old seats, gasoline, and fish even though the side windows had long been removed.

Ed closed the door and looked around. No seatbelts, of course not. He inserted the key and turned. The motor growled and caught after a few puffs. By now, two dozen men stood around in the courtyard, in groups or alone, helplessly looking on, trying to match what their bosses had been shouting at each-other with the fact that the Farangs now appeared to be escaping with the boss-boss. Was this as planned, and good for them, or rather not? In any case, it was too late for actions.

Those who stood between truck and exit, hastily stepped aside, clearing a path but nobody moved to open the gate.

“Tell them to open up,” said Lizzy and elbowed Mr. Ugly.